Locked Toilets and Lost Keys for the Swaccha Bharat Mission

Toilets, though constructed under SBM, are often left locked and unused. In one village near Jhansi, a community toilet with SBM branding was found locked, with no access due to a lost key. The article explore broader aspect of SBM-G

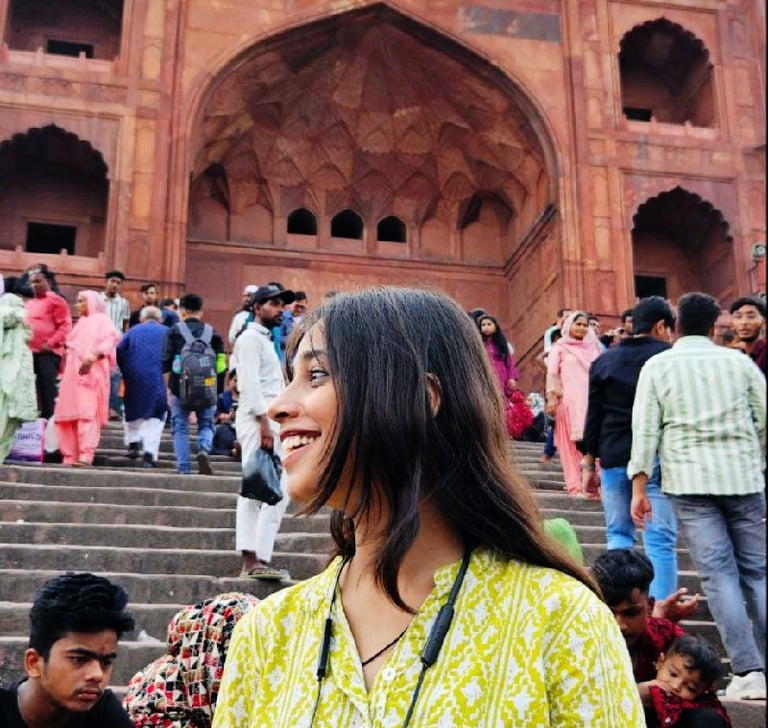

I grew up in Jhansi and the hustle and bustle of this historical city defined my understanding of the world. The concept of a village was very different from the pace and lifestyle of this city and it was something I had only read about in books or seen in films. My recent association with PALIprayas, an organization advocating for sustainable and eco-friendly practices, allowed me to step beyond my comfort zone and explore rural India. It is about a journey of me when I decided to visit a village south of Jhansi to understand the ground reality of the Swachh Bharat Mission (SBM), a flagship initiative launched in 2014 to make India open defecation-free (ODF) which is a status where no individual in a community practices open defecation, ensuring improved hygiene and sanitation

The journey began with much excitement in the last week of December 2024. My focus was simple: to observe and understand the status of toilets built under the SBM, which the government proudly declared a success in October 2019. The numbers looked impressive on paper—100% of villages declared ODF, billions allocated for infrastructure, and campaigns heralded across the country. However, after the visit, I am sure that statistics often tell a partial story.

My First Impressions of a Village Visit

I was accompanied by one of my friend and upon reaching the silence of the village I could Fields stretched as far as my eye could see, with small clusters of houses. Sarson ke khet, like in a Bollywood movie starring Shah Rukh Khan, stretched endlessly before me with golden moments. The words "dharti sunehari, ambar neela" rang in my head, making me believe, just for a moment, that I was the main character in a cinematic masterpiece.

My friend, who was with me, pointed out the community toilet which was a solid structure bearing the emblem of the SBM. Slogans promoting cleanliness adorned its walls in bright colors, proclaiming, “Swachh Gaon, Swasth Gaon” (Clean Village, Healthy Village), and “Sauchalaya ke aaspass nahi rahega gandagi ka vaas” (No dirt will remain near the toilets). At first glance, it seemed like the government’s efforts had indeed reached the grassroots.

But when I tried to see it from the inside, the toilets were locked. When I asked the villagers for the key, they shrugged and told me it had been lost months ago. One of the villagers then gave us directions to the sarpanch's home. Upon reaching, the sarpanch seemed reluctant to open the toilets, brushing it off as unnecessary. After much persuasion and explaining that it was for my college project and we are students and this is not an inspection, he finally agreed.

The scene inside was disheartening. The toilets were far from functional. Instead of providing a basic human need, the structure was a shelter for cows. Fecal matter and animal waste were scattered across the floor, and there were no signs of maintenance or upkeep.

When I asked the sarpanch why the toilets were locked and neglected, his response shocked me:

“Why should we keep them open? No one uses them. People are used to going to the fields.”

This single statement encapsulated a significant problem—one that no amount of funding or infrastructure could solve. The habit of open defecation, deeply ingrained in rural culture, was not addressed through adequate behavioral change initiatives.

While the government declared India ODF in 2019, data from the National Family Health Survey 5 (2019-21) paints a different picture. According to the survey, 19% of all households still practiced open defecation—26% in rural areas and 6% in urban areas. These numbers are not mere statistics; they reflect the disconnect between policy and practice.

One of the key focuses of SBM Phase I was the promotion of twin-pit technology—a sustainable method of waste management where two pits are alternately used for fecal sludge. The filled pit decomposes into organic manure over time, making it a safe and eco-friendly solution. However, the Standing Committee on Rural Development reported that most toilets were built with single pits, which are prone to overflowing and require manual cleaning, perpetuating the inhumane practice of manual scavenging.

Retrofitting these single-pit toilets into twin-pit systems was an essential part of Phase II of SBM, but there has been little to no progress on this front. Even in villages like the one I visited, awareness about such technologies was minimal.

Voices from the Ground

I spoke to several villagers to understand their perspective. An elderly farmer said:

“Humare dada-dadi se le kar hum sab khet mein hi jaate hain. Itna paisa kharch karke ye shauchalaya banwaya, par kaun samjhaye ki kyu istemal karein? (Our grandparents, parents, and we have always used the fields. They spent so much money on these toilets, but who will explain why we should use them?)”

A young woman added, “Shauchalaya toh ban gaya, par pani kahan hai? (The toilet is built, but where is the water?)” This highlighted another glaring issue—the lack of supporting infrastructure like water supply. Without water, toilets are rendered useless, pushing people back to old habits.

Money spend under SBM

The government has allocated Rs 1.4 lakh crore for Phase II of SBM (2020-25), focusing on solid and liquid waste management. For the financial year 2024-25 alone, Rs 7,192 crore has been allocated to SBM-Grameen. While the funding appears robust, the lack of monitoring and accountability has resulted in poorly maintained infrastructure like the one I witnessed.

After the visit I believe, The government’s efforts to build toilets at breakneck speed overlooked critical aspects:

Behavioral Change: Building toilets is only half the battle. Educating people about the health benefits of using toilets and breaking deep-rooted habits requires sustained efforts.

Maintenance and Monitoring: Once toilets are built, who ensures they are functional? Without regular monitoring, these structures fall into disrepair, as seen in the village I visited.

Access to Resources: Toilets require water and proper waste management systems. Without these, the infrastructure is incomplete.

Closing Thoughts

As I left the village, I couldn’t help anything but feel a mix of frustration and hope. The Swachh Bharat Mission is a commendable initiative, but its implementation leaves much to be desired. Villages like the one I visited serve as a stark reminder that change cannot be enforced from the top down. It requires collective effort, cultural shifts, and accountability at every level.

The SBM’s slogan, “Ek Kadam Swachhta Ki Ore” (One Step Towards Cleanliness), resonates deeply. But for that step to have a lasting impact, it must be taken together—with the government, local authorities, and citizens walking hand in hand.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR